Do you ever wonder why trout will take a certain fly one time and not another? Why will an attractor pattern sometimes work, and sometimes it doesn't? To answer these questions, we're going to metaphorically don our trout vision goggles, i.e. looking at flies through a trout's eyes by examining the trout's behavior and senses. One of the key points we will discover along the way is that you will be more successful fishing with specific imitations than with using generic or attractor flies. Specific imitations are those fly patterns that represent a specific species of insect at a specific stage in its life cycle, vs. generic flies, which represent a broad range of insects.

Some Basics - Trout Learning

Though trout may have very small brains, they are able to learn experientially. However, they depend on their instincts and senses, rather than on some sort of analytical intelligence. In other words, from the time they are fry, trout begin “learning” in Pavlovian fashion what items in the stream they should eat, and which ones they should let drift by. Consequently, flies that most specifically resemble the insects the trout are feeding on produce the best results for the fly fisherman.

Feeding Zones

The ideal scenario for a feeding trout is to position itself in slow or moderate current, holding itself in place with minimal energy expenditure, and to have good access to food. This allows the trout to ingest more calories in the food they grab than they expend fighting current. Good positions for the trout include along the stream bottom, behind large rocks, boulders, logs, etc., or just outside of the main current in a slower current. Trout in these areas, so long as they are close to where the food is drifting along, will be able to spend the majority of their time in a low energy state, darting out to ambush a morsel periodically.

Often, currents concentrate insects in drift lines as the insects are carried downstream. Trout take advantage of these drift lines, by positioning themselves nearby in an area of slower moving water (as mentioned above), and being sure that they are able to see what is coming down the drift lines.

Note that certain types of insects will be found in specific types of water/areas of the stream. Therefore, for optimal success while fishing, you should not only use flies that specifically imitate the insects, but you should also fish these flies in the areas of the stream in which the corresponding insects are found. This is why Troutprostore.com offers specific insect patterns with detailed information on how to fish them. Notice, for example, the level of detail of the stonefly nymph below.

Seeing underwater sources of food, such as larvae, pupae, and nymphs in the drift lines depends on water clarity, current, lighting, and background. Trout in clear, well-lit water should be able to notice food items several feet away. Seeing objects above the water, or floating on the surface of the water, is much more complicated. Just think of looking around underwater in a swimming pool. The objects in the pool are probably all visible from a single location in the pool. Objects outside of the water are not quite so easy. These objects must be located in what is known as the window of vision.

Physics - Window (Cone) of Vision

Now let's discuss the underlying physics behind a trout's ability to see objects on top of the water – the window of vision. I had to spend a lot of money and pursue an engineering degree in college to receive an education in optics. Fortunately, you're not going to have to go that route – at least not as far as the optics that relates to trout is concerned.

The window of vision has to do with what portion of the area above the surface of the water that the trout can see from his position below the surface of the water. You may be tempted to think that it is possible to see the entire above-water horizon from a his position underwater, but this is not the case. This is due to the principle of refraction, or bending of light, as it transfers from air to water. You can observe the principle of refraction by placing your fly rod or a pencil into water at an angle, and looking at how it seems to bend at the surface of the water.

If you're an aspiring physics nerd, you can look up Snell's Law, index of refraction, and trigonometric functions to gain an understanding of how this works. For the rest of you, just know that anytime light passes from one medium, such as air, to another, such as water, its speed changes. This change of speed can cause the light to bend. An exception to this is if the light is traveling perpendicular to the intersection of the two media, such as light that is traveling straight down into the water. In this case, the light changes speed but does not bend.

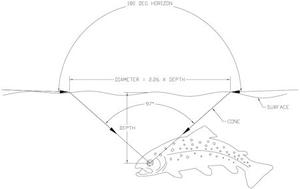

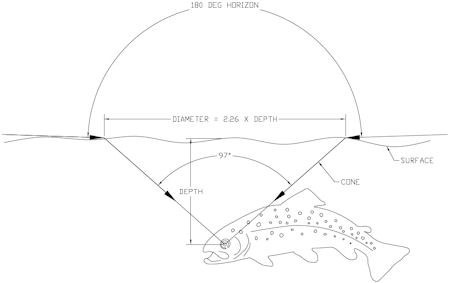

The area above the water that a trout can see from his position underwater is condensed to 97 degrees of vision. Choppiness at the water's surface complicates matters, as you can imagine. For simplicity's sake, we will only discuss the smooth water surface condition. This 97 degrees of vision forms a cone shape in three dimensions. Anything visible outside of this cone comes from light reflected from underneath the surface of the water, not from above the surface of the water.

Note that the diameter of the circular area at the top of the cone/surface of the water (i.e. the area in which the trout can see objects on the surface) is larger the deeper the trout is. In fact, thanks again to the miracles of physics and math, we know that the diameter of this circular area is 2.26 times the depth of the trout's eyes. Again, anything visible outside of this area on the surface of the water is from light reflected from under the surface of the water. Refer to the illustration below.

So, if this were a math textbook, we would work out an example problem at this point: If a trout's eyes were 18 inches below the surface of calm water, how far upstream and downstream would an object on the surface of the water be visible to it? The answer is that the total length of visibility would be 2.26 X 18 inches = 40.7”. This means the object, perhaps a dry fly from Troutprostore.com, would be visible to the trout from approximately 20” upstream of the trout to 20” in downstream of the trout. Note that it also means that an object 20” to the side of the trout on the surface of the water would also be visible.

Practically, what this means is that a trout near the surface of the water has a much narrower and shorter feeding lane/area than one that is deeper. If your fly lands too far to the side, the trout will not see it, for example. Therefore, you want to position yourself to make good casts, hitting the target zone. If, however, you miss the target zone, allow your fly/line to drift downstream far enough that you will not scare the fish as you begin your backcast.

Another funky aspect of the physics is that the further an object is from the center line of the cone of vision, the more distorted it appears to be. This is because the light from that extreme angle is bent more than the light near the center of the cone is. This means your fly will actually have the appearance of changing its shape as it floats along. However, despite the distortion that occurs away from the center of the cone of vision, you should not underestimate the importance of using imitative flies. The real insects will also distort in appearance, and your fly should be as close an approximation to the real thing as possible.

Summarizing:

Trout will ideally position themselves in slower moving water often deeper in the water column where they are able to see more of the area above the surface of the water. The biggest trout enjoy these positions so be careful stalking these wary trout, and to ensure the most success use specific fly patterns on troutprostore.com.

The further from the center of the cone of vision an object is, the more distorted it appears to be. However, the trout will reposition himself to better examine the fly, and that is when the advantage of imitative flies will prevail. How many times have you seen a trout examine a fly and them swiftly move away?

Check out our amazing Underwater World of Trout DVD's, offered both individually and as a collection, featuring fantastic underwater video of trout in their habitat.

Want more? Subscribe to our email list to receive the final two parts in this three part series.

In the next article, we examine how flies interact with the surface film, the trout's binocular and peripheral vision, dapping, lighting, and the effects of water speed. Learn how this knowledge will make you a better fisherman.